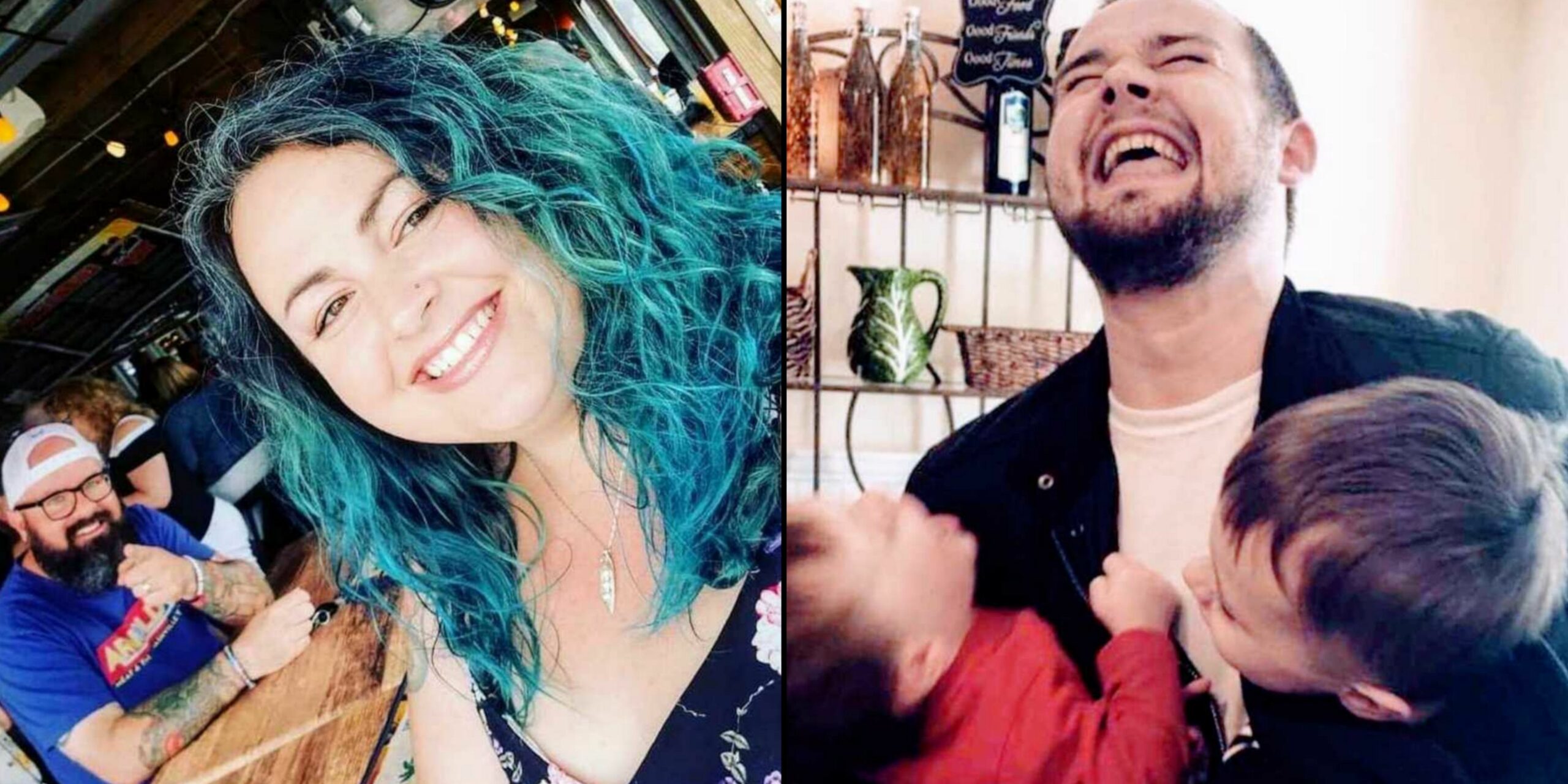

September 13th will mark two years since I lost my little brother, Andrew Carter, to addiction. He was only 25. That day, he slipped from recovery, using cocaine that was unknowingly laced with fentanyl, and died that very night. None of this reached me in time; I had no idea what had happened.

The next morning, I was experiencing one of my best mornings as a mom. It was the first time both of my boys were in school and preschool all day, giving me a rare stretch of quiet. I reveled in the freedom—stopping at Starbucks, the grocery store, Sam’s Club, and running errands without interruption. The peace felt almost euphoric.

Then, my phone rang. It was my mom and sister. My brother had been found dead. I was in the grocery store checkout line when the words hit me, and for a moment, I couldn’t process them. Shock, disbelief, and numbness washed over me. I always imagined that if this day ever came, I would collapse, wail, and scream—but instead, I uttered, almost mechanically, “What do you mean he’s dead?” My voice, I later realized, wasn’t just loud—it screeched, piercing the ordinary calm of the store.

Somehow, I made it to my car with my groceries. A kind stranger helped me load them, though I barely registered it. On autopilot, I even stopped for gas, calling my husband, Nathan, out of state to share the devastating news. When I hung up, the grief finally broke through. An elderly man approached me at the pump, offering help. I told him I needed my dead brother back. He prayed for me right there, and for that brief moment, I felt a thread of humanity and compassion.

Because my trauma struck in the middle of everyday errands, I unknowingly developed deep anxiety around normal, mundane tasks. The first time I went out alone afterward, I had a full-blown panic attack in the towel aisle at Walmart. My mind irrationally convinced me that something terrible would happen while I was away from home—that I might receive more devastating news or lose someone else I loved. Every stranger felt like a potential threat, every moment of normalcy seemed dangerous. I realized I needed to learn how to cope quickly—especially with Nathan often on the road.

I found grounding through constant distraction. I began wearing earbuds everywhere—music, audiobooks, anything loud enough to shield me from my surroundings. It allowed me to focus on tasks while ignoring the watching eyes and curious stares. At home, I even used this technique to distance myself from my grief, much to Nathan’s frustration. But he understood, giving me space before gently helping me wean off the crutch so I could face my pain head-on.

Another outlet became tattoos. As a teen, I had engaged in self-harm, unable to process toxic emotions safely. I started getting tattoos at 18, never realizing how therapeutic the process could be. The controlled, cosmetic pain released negativity I had been carrying, and unlike scars, left behind beautiful artwork. In memory of Andrew, I got a tattoo that incorporated a wooden spoon from a family joke and the symbol for recovery, honoring both him and my commitment to support others in their journeys.

Am I “cured” now? No. I still avoid public interactions when possible, often consolidating errands to minimize exposure. I sometimes choose my home, dogs, art studio, or garden over crowded stores. Yet, I still go out, attend concerts, see friends, and even speak publicly when needed for work. I function, but not every day is easy. I’ve learned that being high-functioning with mental illness doesn’t mean I’m untouched—it just means I’ve found ways to navigate it.

I share this in hopes that someone reading will gain understanding—about themselves, a friend, or a loved one. Perhaps now it makes sense why someone always wears headphones, or chooses tattoos, or appears withdrawn. Knowledge is a powerful tool. When we comprehend the experiences of others, we can respond with compassion instead of judgment. Safe spaces, mental health accommodations, and trauma-informed care aren’t luxuries—they’re lifelines. They allow people to function, heal, and break cycles of inherited trauma. We cannot suppress our pain without consequences; we must face it, actively and healthily, if we want to change the world for the better.